The Agglestone is one of Purbeck’s curious and quirky landmarks that have been delighting – and puzzling – people for generations.

Located in the middle of the vast Godlingston Heath, this imposing presence on the landscape has wide-reaching views down to Studland Bay and across to Little Sea and Poole Harbour.

It is not known how the huge, iron-rich sandstone came to be sitting in its solitary way on its small hill in the Purbeck landscape, but its presence has been shrouded in mystery for generations.

There are many myths and legends surrounding Agglestone Rock.

Mythology, geology & human intervention

The story of this imposing rock that looks like it fell out of the sky is as mysterious as it is large – estimated to be around 400 tonnes.

Whilst the true origins of Agglestone Rock may be lost in the depths of history, there are some favoured stories that have prevailed over the years, as well as some evidence that it was important to humans at various points.

The “Devil’s Anvil”

Legend has it that the Agglestone was thrown over from The Needles on the Isle of Wight by the devil himself (‘Agglestone’ taken to mean “Devil’s Anvil”).

The rock was once in fact anvil-shaped but succumbed to the elements over the years and toppled onto its side toward the south-east.

Some say the devil, enraged by the striking keep of Corfe Castle, aimed a missile at it, but it fell short, turning to stone on the heath. Other stories say that Satan was carrying the huge rock as he flew through the air to drop onto Salisbury Cathedral or even Bindon Abbey, again jealous of their impressive architecture, but that its weight was too heavy and he dropped it over Studland.

A Druids’ altar

There are various pagan stories surrounding Agglestone Rock. With its relatively flat surface (before it fell over) the rock was said to have been used as an altar by the Druids.

Other outdated beliefs include alternative explanations of the presence of the Aggelstone, with its name believed to be derived from the Anglo-Saxon words hagge, meaning ‘witch’ and stan, meaning ‘stone.’

There is also an extract written in the 1800s that refers to it once also being known as the Adlingston, and as possibly being named ‘Holy home’, after the Saxon halig-han.

A quarrying relic?

It’s clear that the shape and inclination of the Agglestone has changed through natural processes over time, however there is some evidence that it may also have altered shape due to human activity. It is believed there may have been minor quarrying of the stone, further enhancing its upside-down conical shape.

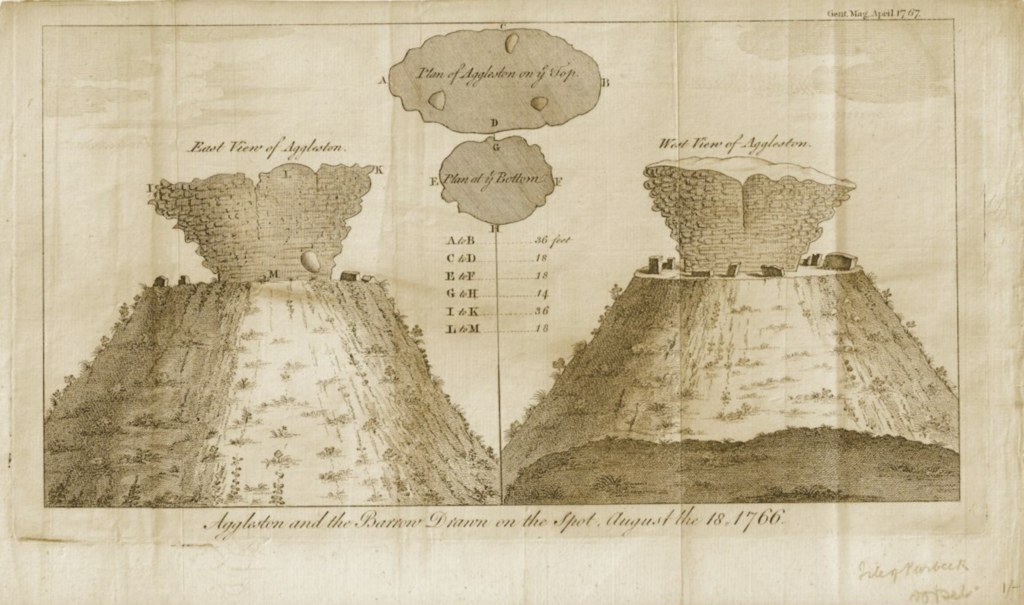

But quarrying of the rock itself doesn’t explain the distinctive shape, nor why in the below illustration there are eight blocks of seemingly quarried stone positioned around the Agglestone in a circular fashion.

It has been suggested that Agglestone Rock was actually part of a wider quarrying project in the area, and left as a relic by quarrymen, as they often did (a nearby famous stone quarry relic is that of the St Aldhelm’s Head monolith.)

We do not know what, if any, quarrying history is attached to the rock, but it is widely agreed that it is likely to simply be a natural feature of the Purbeck landscape, which may have been ‘tinkered’ with and used in different ways by different peoples at various points in history.

Today it is a unique landmark that captures the imagination of walkers, cyclists and horse-riders in this Thomas Hardy-esque landscape.

Some people do also use the Agglestone as a rock-climbing crag and, if you visit it, you’ll see that many other visitors have carved their initials into the sandstone, however in order to preserve this special part of Dorset for generations to come it is recommended to treat it with respect and admire it from a sensible distance.

Godlingston Heath

The dramatic Godlingston Heath is part of the National Trust-managed Studland Nature Reserve.

Depending on the time of year you come, the heath will be carpeted in swathes of purple heather, with 360° views from the Agglestone.

The nature reserve provides important habitats for wildlife, and is home to all six of the UK’s native reptiles. It also forms part of the newly-created Purbeck Heaths ‘super’ nature reserve – Britain’s first of its kind.

Purbeck Heaths include Studland & Godlingston Heath, the Arne Peninsula and nature reserve, and Hartland Moor, and is regarded as one of the most biodiverse areas in the UK.

How to find the Agglestone

Agglestone Rock can only be reached on foot.

There are a number of walking routes from Studland village through the wildlife-rich heathland.

There is also a quicker route that can be taken from a small lay-by parking area on the B3351 Corfe – Studland road. Note that this section of the road is quite narrow and there may be fast cars approaching.

From Studland village

Park at Middle Beach car park (postcode for SatNav: BH19 3AX) and walk back up past Studland Stores and toward Agglestone Road, which will lead to a track onto Godlingston Heath.

You’ll be able to see the rock in the distance, so head toward it, keeping to the path and turning right at the gravel track and crossroads.

You can make this a circular walk back to your car, which will take around an hour and a half.

From the B3351

A few hundred metres past the Isle of Purbeck Golf Club (SatNav postcode: BH19 3AB) on the B3351 is a public bridleway through the heath directly to the Agglestone, with waymarkers to guide you.

There is limited parking here for a small number of cars. Care should be taken when leaving this parking spot.

Nearby unusual natural landmarks

One of the reasons people flock to the Jurassic Coast each year is because of the beautiful and often unusual landmarks in the landscape.

You’ll find many interesting rock formations and natural wonders around Purbeck. Some have been formed naturally and some through human – and even dinosaur – intervention.

Some of the most famous natural landmarks on the Dorset coast include Old Harry Rocks, Durdle Door and Lulworth Cove, where you’ll find further intriguing geological features and formations such as the Lulworth Crumple, Stair Hole and the Fossil Forest. Exploring further around Purbeck you can see the strata in the rocks at Kimmeridge, which is abundant with fossils. There are even sites where you can see the remains of dinosaur footprints, near the villages of Worth Matravers and Langton Matravers.

Echoes of the humans of the past can also be seen in the landscape, especially with the Isle of Purbeck‘s rich quarrying history – check out the now disused quarrying caves of Winspit, or view the imposing St Aldhelm’s Head monolith.